Sleep deprivation doesn't just make you tired; it fundamentally impairs your ability to learn, remember information, regulate emotions, and make good decisions. When chronic sleep loss results from genuinely unsustainable academic demands rather than poor time management, using professional essay writing for lower-stakes assignments during particularly demanding weeks can preserve the sleep hours essential for cognitive function and long-term health rather than sacrificing rest to meet impossible deadlines.

This guide reveals evidence-based strategies for improving sleep quality and duration, how sleep directly impacts academic performance and health, practical techniques for falling asleep faster and staying asleep, and when sleep problems signal deeper issues requiring professional intervention.

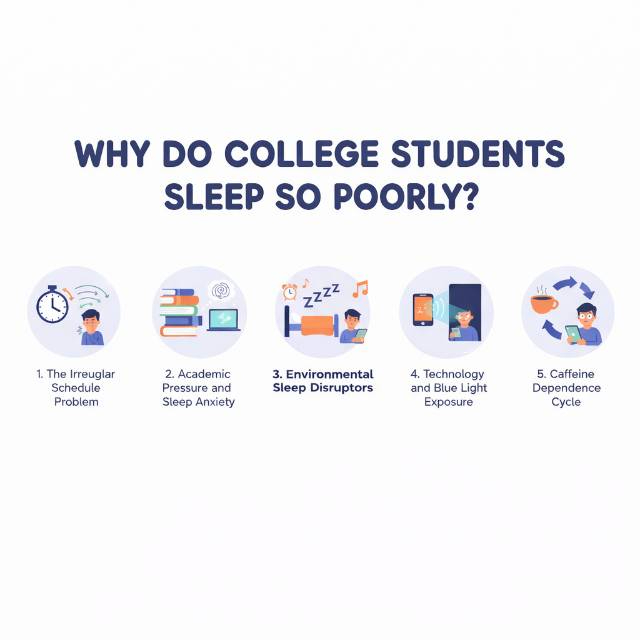

Why Do College Students Sleep So Poorly?

College students sleep poorly due to irregular schedules where class times, work shifts, and social activities vary daily preventing consistent sleep-wake patterns that regulate circadian rhythms, academic pressure creating anxiety that interferes with falling asleep and causes middle-of-night waking, environmental factors including noisy dorms, uncomfortable beds, and roommates with conflicting schedules, excessive screen time before bed suppressing melatonin production through blue light exposure, and caffeine consumption patterns where students drink coffee or energy drinks late afternoon or evening to combat tiredness then can't sleep at night.

Research on college sleep reveals that 70-80% of students report difficulty falling asleep at least twice weekly, with 50-60% experiencing middle-of-night waking they can't explain, and sleep quality ratings averaging 4-5 out of 10 compared to 6-8 for non-student adults in the same age group.

1. The Irregular Schedule Problem

Your body's circadian rhythm thrives on consistency, but college schedules change daily. On Monday, you wake at 7 AM for an 8 AM class. Tuesday, your first class starts at 11 AM, so you sleep until 9:30. Wednesday brings early morning again. This variation confuses your internal clock, making it impossible to establish natural sleep-wake patterns. Your body never knows when it should feel sleepy or alert.

Research shows that students with class schedules varying by more than 2 hours daily experience 30-40% worse sleep quality than those with consistent morning or afternoon schedules. Weekend schedule shifts compound the problem as sleeping until noon Saturday and Sunday creates "social jet lag" requiring Monday and Tuesday to readjust.

Work shifts create additional irregularity, especially for students working closing shifts ending at 11 PM or midnight, then trying to sleep immediately. Your body needs 2-3 hours to wind down from work activity before sleep becomes possible. Students working variable shifts report 40-50% higher rates of insomnia compared to those with consistent schedules or no employment.

Social schedules also disrupt sleep as college culture normalizes staying up late for social activities, gaming, or hanging out with friends. The perception that "everyone" stays up until 2 AM creates pressure to match that pattern even when your body needs earlier sleep. Studies show that students in single rooms sleep 45-60 minutes more nightly on average than those with roommates whose schedules differ from theirs.

2. Academic Pressure and Sleep Anxiety

Stress about grades, assignments, and future career prospects keeps your mind racing when trying to sleep. You lie in bed mentally reviewing everything you should have done that day or worrying about tomorrow's exam. This anxiety triggers your sympathetic nervous system, keeping you in fight-or-flight mode, incompatible with sleep.

Research indicates that 65-75% of college students report lying awake thinking about academic concerns at least three nights weekly. The anxiety becomes self-perpetuating as worrying about not sleeping makes falling asleep harder, creating frustration that further prevents sleep.

Procrastination creates sleep-disrupting deadline pressure. When you delay starting assignments until the last minute, sleep becomes the first thing sacrificed to meet deadlines. The pattern repeats as sleep deprivation reduces your executive function, making procrastination worse, leading to more last-minute cramming and less sleep. Students who chronically procrastinate average 60-90 minutes less sleep nightly than those who work steadily on assignments.

All-nighters and near-all-nighters disrupt sleep for days afterward. Staying up until 3-4 AM studying throws off your circadian rhythm, requiring 3-4 days to fully recover. Studies show that students who pull all-nighters perform 20-30% worse on exams taken within 24 hours compared to peers who slept normally, despite spending more total study time.

3. Environmental Sleep Disruptors

Dorm rooms often provide terrible sleep environments. Thin walls transmit neighbor noise. Bright hallway lights shine under doors. Heating and cooling systems create either too-hot or too-cold temperatures. Research shows that 55-65% of college students rate their dorm sleep environment as poor to fair compared to their home bedrooms. Roommate incompatibility creates major sleep problems when one person goes to bed at 10 PM while the other stays up working with the lights on until 2 AM. Studies indicate that roommate schedule mismatches reduce sleep duration by 45-75 minutes nightly on average.

Uncomfortable mattresses, common in dorms, prevent deep sleep. Your body needs to fully relax to enter restorative sleep stages, but uncomfortable beds keep you partially tense throughout the night. Most college students report their dorm mattresses as significantly less comfortable than their home beds. The combination of poor mattress quality, unfamiliar sleeping environments, and environmental noise means dorm sleep quality rates 30-40% lower than home sleep for most first-year students.

Shared bathrooms create additional challenges as bathroom trips at night fully wake you, rather than allowing easy return to sleep. Late-night bathroom traffic and door slamming disturb light sleepers. Temperature control issues, where you can't adjust your room's temperature to optimal sleep ranges of 60-67°F, prevent your body from cooling properly for sleep initiation.

4. Technology and Blue Light Exposure

Screens emit blue light that suppresses melatonin production, signaling your body that it's daytime. When you scroll social media or watch videos before bed, you're actively preventing your brain from entering sleep mode.

Research shows that 2 hours of screen exposure before bed delays melatonin release by 60-90 minutes, meaning you won't feel sleepy until much later than without screens. Even 30 minutes of phone use before bed suppresses melatonin by 20-30% for 1-2 hours afterward.

The content you consume matters beyond just light exposure. Engaging social media posts, stressful news, or exciting shows activate your mind, making it harder to relax into sleep. Students who use phones in bed report taking 25-40 minutes longer to fall asleep on average than those who stop screen time 60+ minutes before bed. The temptation to "just check one thing" leads to 30-60 minutes of scrolling that directly steals sleep time.

Sleeping with phones nearby creates sleep disruption even without active use. Notifications, buzzing, and screen lighting from incoming messages wake you from light sleep stages, preventing progression to deep restorative sleep. Studies show that students who sleep with phones on silent mode in another room sleep 30-45 minutes more per night than those with phones on nightstands.

5. Caffeine Dependence Cycle

Sleep deprivation drives caffeine consumption, which further disrupts sleep, creating a vicious cycle. You sleep poorly, so you drink coffee to function. The caffeine stays in your system 6-8 hours, preventing sleep that night. You sleep poorly again, requiring more caffeine the next day.

Research indicates that 75-85% of college students consume caffeine daily, with 30-40% consuming it after 2 PM when its half-life of 6 hours means significant amounts remain at bedtime.

Caffeine tolerance develops with regular use, requiring increasing amounts to achieve the same alertness effect. Students who drink 3-4 cups daily experience significantly less cognitive boost than occasional caffeine users getting the same dose. Yet the sleep-disrupting effects remain constant regardless of tolerance. You need more caffeine to feel awake, but it still prevents sleep at night.

Energy drinks containing 150-300mg of caffeine per serving, plus sugar and other stimulants, create particularly severe sleep disruption. Students consuming energy drinks after 4 PM report 50-70% longer sleep onset times and 30-40% more nighttime waking compared to those avoiding late-day caffeine. The combination of high caffeine doses and sugar crashes creates unstable energy patterns throughout the day.

Sleep Myths vs. Sleep Facts (Quick & Clear)

Sleep Myth | Real Sleep Facts |

You can train yourself to need less sleep • Less sleep = poorer focus & memory • Performance drops after 5–6 hours/night | • Adults still need 7–9 hours |

Catching up on weekends works • Disrupts body clock (“social jet lag”) • Monday fatigue increases | • Recovers only 25–30% of lost sleep |

Sleeping at random times is fine • Irregular sleep lowers academic performance • Increases daytime tiredness | • Consistency matters more than total hours |

Snoring is harmless • Affects focus & heart health • Often goes undiagnosed | • Can signal sleep apnea |

Alcohol improves sleep • Causes lighter, broken sleep • Worsens next-day fatigue | • Reduces REM sleep |

Phone use before bed doesn’t matter • Delays sleep onset • Reduces deep sleep quality | • Blue light lowers melatonin |

Staying in bed awake still helps • Bed-brain association weakens • Get up after 20–30 minutes | • Increases sleep anxiety |

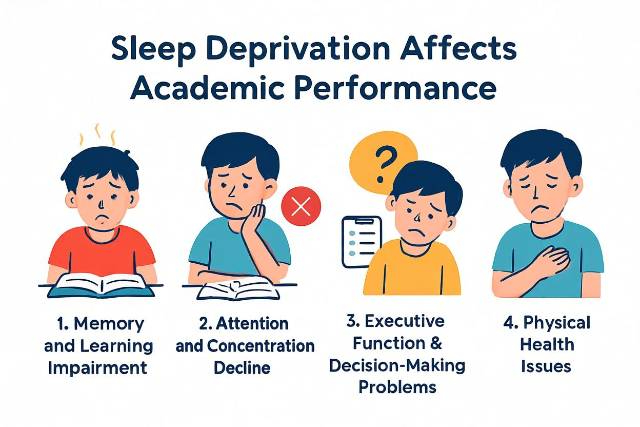

How Does Sleep Deprivation Affect Academic Performance?

Sleep deprivation impairs academic performance by reducing memory consolidation where information studied doesn't transfer from short-term to long-term memory making retention 25-40% worse after inadequate sleep, decreasing attention span and focus causing 30-50% more errors on tasks requiring sustained concentration, impairing executive function reducing ability to plan, organize, and make good decisions, slowing information processing speed where sleep-deprived students take 20-35% longer to complete cognitive tasks, and weakening emotional regulation increasing impulsive decisions and stress responses that interfere with learning.

Studies comparing academic outcomes show students averaging 7-9 hours nightly maintain GPAs 0.3-0.5 points higher than those averaging less than 6 hours, with differences most pronounced in courses requiring complex reasoning, memorization, or mathematical problem-solving rather than simple rote tasks.

1. Memory and Learning Impairment

Sleep is when your brain consolidates memories, transferring information from temporary storage to long-term memory. During the deep sleep stages, your brain replays and strengthens neural connections formed during studying. Without adequate sleep, this consolidation doesn't occur effectively.

Research shows that students who sleep 4-5 hours after studying retain only 60-70% of material compared to 85-95% retention for those sleeping 7-8 hours. This means hours spent studying provide less actual learning benefit when followed by insufficient sleep.

Different sleep stages serve different memory functions. REM sleep consolidates procedural memories like problem-solving approaches and creative connections. Deep non-REM sleep consolidates declarative memories like facts and concepts. Getting only 5-6 hours of sleep cuts into these crucial stages, preventing proper memory formation. Studies demonstrate that students who pull all-nighters before exams score 20-30% lower on average than peers who stopped studying at midnight and slept 7-8 hours, despite the all-nighter group having more total study time.

The timing of sleep relative to learning matters significantly. Sleeping within 12 hours of studying improves retention by 30-40% compared to staying awake more than 12 hours after learning. This explains why cramming the night before works better than cramming two days before; the proximity of sleep to studying enhances consolidation. However, sleeping poorly the night after learning still impairs memory even if you slept well the night before studying.

2. Attention and Concentration Decline

Sleep deprivation severely impairs your ability to maintain attention during lectures and reading. Your mind wanders more frequently, requiring rereading paragraphs multiple times.

Research shows sleep-deprived students experience 40-60% more attention lapses during 50-minute lectures compared to well-rested peers. These microsleeps, where you zone out for seconds, happen without awareness, meaning you miss information without realizing it.

Sustained focus becomes nearly impossible with chronic sleep debt. Tasks requiring extended concentration, like writing papers or solving problem sets, take significantly longer when sleep-deprived. Studies indicate that assignments requiring 3 hours of focused work take 4-5 hours when completed on insufficient sleep due to frequent breaks, distraction, and rework from errors made while unfocused.

The subjective feeling of alertness doesn't match objective performance. You might feel "fine" after 5-6 hours of sleep, but testing reveals 25-35% slower reaction times and 30-40% more errors compared to your well-rested baseline. This mismatch means you don't realize how impaired you actually are, leading to overconfidence in your ability to perform complex tasks while sleep-deprived.

3. Executive Function and Decision-Making Problems

Executive function encompasses planning, organization, prioritization, and impulse control, all critical for academic success. Sleep deprivation significantly impairs these higher-order cognitive abilities.

Research shows that students operating on 5-6 hours of sleep demonstrate 30-40% worse performance on executive function tasks, including planning project timelines, prioritizing multiple deadlines, and making strategic study decisions.

Poor sleep leads to worse decision-making around time management and studying. You choose easier tasks over important ones, procrastinate on challenging work, and make impulsive decisions about how to spend time. The prefrontal cortex responsible for executive function, is particularly vulnerable to sleep deprivation, showing decreased activity on brain imaging after just one night of inadequate sleep. Studies reveal that sleep-deprived students are 40-50% more likely to make poor academic choices like skipping class, missing deadlines, or cramming rather than spacing study sessions.

Risk assessment becomes impaired with sleep loss. You underestimate how long assignments will take, overestimate your ability to multitask, and fail to recognize when you're too tired to work effectively. This leads to patterns like staying up late working when you'd learn more efficiently by sleeping and waking early. Research indicates that sleep-deprived students show 35-45% worse judgment about their own cognitive state compared to well-rested peers.

4. Physical Health Consequences Affecting Academics

Sleep deprivation compromises immune function, making you more susceptible to illnesses that cause class absences. Studies show that students averaging less than 6 hours nightly have 3-4 times higher rates of cold and flu infections compared to those sleeping 7-9 hours. Each illness typically causes 2-3 missed class days and reduced cognitive function for 5-7 days total, significantly impacting academic performance.

Chronic sleep loss increases stress hormone cortisol levels, which interferes with learning and memory while increasing anxiety. Elevated cortisol makes you feel more stressed about academic demands while simultaneously reducing your cognitive capacity to handle them.

Research reveals that students with chronic sleep debt report 50-70% higher stress levels and 40-50% higher anxiety symptoms compared to well-rested peers, even when facing identical academic workloads.

The relationship between sleep and mental health works bidirectionally. Poor sleep increases the risk of depression and anxiety, while these conditions worsen sleep, creating a negative cycle. Studies indicate that college students with chronic insomnia have 3-4 times higher rates of developing depression or anxiety disorders compared to good sleepers. When workload becomes genuinely unsustainable, preventing adequate sleep, using an essay writing service for strategic support on lower-priority assignments can break the cycle of sleep deprivation impairing performance, which increases stress, which further worsens sleep.

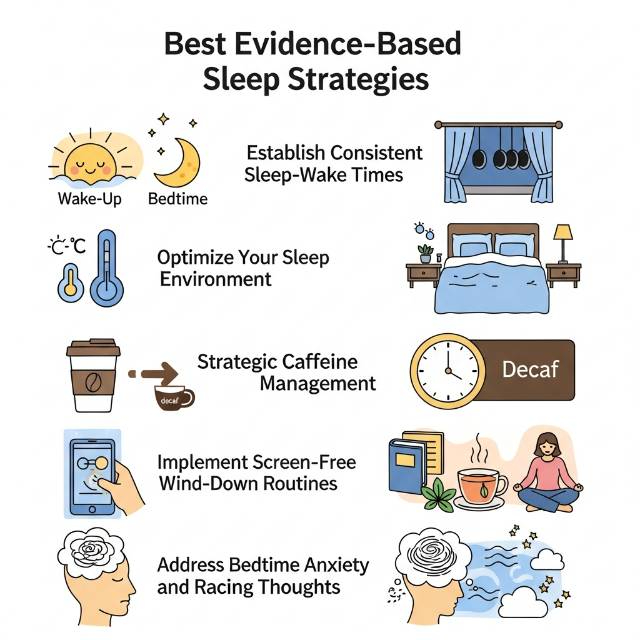

What Are the Best Evidence-Based Sleep Strategies?

The most effective evidence-based sleep strategies include maintaining consistent sleep-wake times within 30 minutes daily even on weekends to stabilize circadian rhythms, creating optimal sleep environments that are dark, cool at 60-67°F, and quiet through blackout curtains, earplugs, or white noise machines, limiting caffeine to morning hours only avoiding consumption after 2 PM, implementing 60-90 minute screen-free wind-down routines before bed, exercising regularly but completing workouts 3-4 hours before bedtime, using cognitive behavioral techniques for insomnia including stimulus control and sleep restriction, and managing stress through relaxation practices that activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

Research on sleep interventions shows that students implementing these evidence-based strategies increase average nightly sleep by 60-90 minutes within 2-3 weeks while improving sleep quality ratings by 40-50%, with sustained improvements in daytime alertness, mood, and academic performance.

1. Establish Consistent Sleep-Wake Times

Your circadian rhythm operates on roughly 24-hour cycles that synchronize with external light-dark patterns. Consistency is crucial for maintaining this rhythm. Going to bed and waking at the same time daily within 30-minute windows helps your body anticipate sleep and wake times.

Research shows that students with consistent schedules fall asleep 15-25 minutes faster on average than those with variable schedules. After 2-3 weeks of consistency, your body naturally feels sleepy at bedtime and wakes before your alarm.

Weekend sleep schedule shifts create "social jet lag" equivalent to traveling across time zones. Sleeping until noon Saturday and Sunday after weekday 7 AM wake times forces Monday and Tuesday readjustment. Studies indicate that students whose weekend wake times differ by more than 2 hours from weekdays report 30-40% worse sleep quality and higher Monday fatigue compared to those maintaining consistent schedules. If you're extremely sleep-deprived on weekends, you likely need to move your weekday bedtime earlier rather than catching up with extended weekend sleep.

Morning light exposure helps reset your circadian rhythm, making consistent wake times easier. Getting 15-30 minutes of bright light within an hour of waking signals your body that it's daytime, strengthening your sleep-wake cycle. Natural sunlight works best, but bright artificial light helps too. Students who get morning light exposure report 20-30% improvement in nighttime sleep quality compared to those who stay in dimly lit environments all morning.

2. Optimize Your Sleep Environment

Temperature significantly affects sleep quality, with research showing optimal sleep occurs in rooms between 60-67°F. Your core body temperature naturally drops 1-2 degrees during sleep initiation. Cool environments facilitate this temperature drop, while warm rooms prevent it, making sleep difficult. Students who lower the room temperature to optimal ranges report falling asleep 10-20 minutes faster on average. If you can't control room temperature directly, use fans for air circulation, sleep with fewer blankets, or try cooling pillows.

Darkness signals melatonin production, preparing your body for sleep. Light exposure suppresses melatonin, keeping you alert. Even small amounts of light from electronics, streetlights, or hallways can disrupt sleep. Blackout curtains or eye masks create complete darkness, improving sleep quality by 25-35% for light-sensitive sleepers. If roommates need lights on late, eye masks provide personal darkness without conflict.

Noise disrupts sleep even when you don't consciously wake. Your brain processes sounds during sleep, with sudden noises pulling you from deep to light sleep stages, reducing restoration. White noise machines or apps provide a constant background sound masking disruptive noises. Earplugs reduce ambient sound by 20-30 decibels, making them highly effective for noisy dorms. Studies show that students using white noise or earplugs in dorm environments increase total sleep time by 25-45 minutes nightly.

3. Strategic Caffeine Management

Caffeine has a half-life of 5-6 hours, meaning that coffee consumed at 4 PM still has 50% of its caffeine in your system at 10 PM.

Research shows that caffeine consumed within 6 hours of bedtime reduces total sleep time by 30-60 minutes and decreases sleep quality by 20-30%. Setting a firm 2 PM caffeine cutoff ensures minimal amounts remain at typical bedtimes. Students who eliminate afternoon caffeine report falling asleep 15-25 minutes faster on average within one week.

Morning caffeine provides maximum benefit with minimal sleep disruption. Drinking coffee within 1-2 hours of waking helps overcome sleep inertia while clearing your system by bedtime. Avoid drinking caffeine immediately upon waking, as cortisol levels peak naturally in the first hour, making caffeine less effective. Waiting 60-90 minutes after waking optimizes caffeine's alertness benefits.

Monitor total caffeine intake as excessive consumption causes jitteriness and anxiety, even when timing is appropriate. Most people tolerate 200-400mg daily, roughly 2-4 cups of coffee. Energy drinks often contain 150-300mg per serving, making it easy to overconsume. Students reducing daily caffeine from 500-600mg to 200-300mg report 30-40% improvement in sleep quality within two weeks, despite initial increased tiredness during the adjustment period.

4. Implement Screen-Free Wind-Down Routines

Blue light from screens suppresses melatonin production for 1-2 hours after exposure. Implementing 60-90 minute screen-free wind-down periods allows natural melatonin rise, preparing your body for sleep.

Research shows that students who stop screen use 90 minutes before bed fall asleep 20-30 minutes faster than those who use devices until bedtime. The transition feels difficult initially, but becomes easier after 5-7 days of consistency.

Replace screen time with relaxing activities that don't activate your mind. Reading physical books, light stretching, journaling, or listening to calm music helps transition to sleep. Avoid stimulating content even in non-screen formats like thriller novels or intense podcasts. The goal is a gradual mental downshift from daytime alertness to sleep readiness.

If eliminating screens completely feels impossible, use blue light filters or glasses that block blue wavelengths. Studies show these reduce melatonin suppression by 40-60% though complete screen avoidance works better. Set devices to night mode, which reduces blue light emission by shifting toward warmer tones. Keep screens at least 12-18 inches from your face, as closer distances increase light exposure to your eyes.

5. Address Bedtime Anxiety and Racing Thoughts

Many students struggle with anxious thoughts that prevent sleep. Cognitive techniques help manage this pattern. The "worry window" technique involves scheduling 15-20 minutes earlier in the evening specifically for thinking about concerns. Write worries down, then set them aside until your designated worry time tomorrow. Research shows this technique reduces bedtime rumination by 40-50% as your brain learns it will have dedicated time to process concerns rather than needing to do it at night.

Progressive muscle relaxation reduces physical tension associated with anxiety. Systematically tense then release muscle groups, starting with your toes and moving upward. This focuses attention on physical sensation rather than thoughts while reducing muscle tension that interferes with sleep. Studies indicate that students practicing progressive muscle relaxation fall asleep 10-15 minutes faster on average.

Box breathing activates your parasympathetic nervous system, counteracting anxiety's fight-or-flight activation. Breathe in for 4 counts, hold for 4, exhale for 4, hold for 4, and repeat. This technique slows the heart rate and promotes relaxation. Research shows 5-10 minutes of controlled breathing before bed reduces sleep onset time by 15-20 minutes for anxious sleepers.

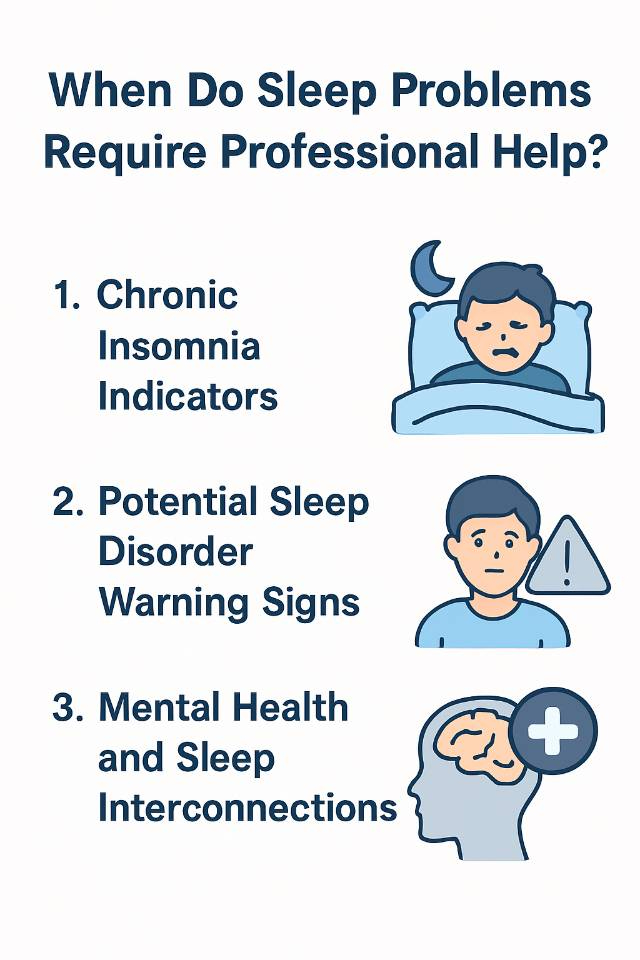

When Do Sleep Problems Require Professional Help?

Sleep problems require professional evaluation when you consistently take more than 30-45 minutes to fall asleep nightly despite good sleep hygiene for more than 3-4 weeks, experience frequent nighttime waking where you're awake for extended periods and can't return to sleep, wake up feeling unrefreshed despite adequate time in bed suggesting poor sleep quality or potential sleep disorders, develop daytime sleepiness severe enough to fall asleep unintentionally during classes or activities, or when sleep difficulties accompany symptoms of depression, anxiety, or other mental health concerns requiring integrated treatment.

Research indicates that 15-20% of college students meet criteria for clinical insomnia requiring treatment beyond basic sleep hygiene improvements, with sleep disorders, including sleep apnea, affecting 5-8% of college-age populations but often going undiagnosed.

Studies show that students with untreated sleep disorders demonstrate 30-40% worse academic outcomes compared to peers with similar abilities but healthy sleep, making professional evaluation critical when problems persist.

1. Chronic Insomnia Indicators

Occasional difficulty sleeping differs from chronic insomnia requiring professional help. Insomnia becomes clinical when sleep difficulties occur at least three nights weekly for more than three months, causing significant daytime impairment.

Research shows this affects 15-20% of college students. Beyond normal sleeplessness, clinical insomnia involves persistent patterns of difficulty initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, or early morning awakening despite adequate opportunity for sleep.

If you've implemented good sleep hygiene consistently for 4-6 weeks, including a consistent schedule, an optimized environment, and appropriate caffeine management without improvement, professional evaluation becomes necessary. Your campus health center likely offers sleep medicine consultations or can refer to sleep specialists. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia proves highly effective, with 70-80% of patients showing significant improvement within 6-8 sessions.

Sleep restriction therapy and stimulus control represent evidence-based insomnia treatments. These techniques seem counterintuitive, like limiting time in bed to consolidate sleep or leaving bed when unable to sleep, but demonstrate 60-70% effectiveness rates. They work best under professional guidance, as improper implementation can worsen sleep initially. Students with chronic insomnia who receive CBT-I report sustained improvements in sleep quality for months to years after treatment.

2. Potential Sleep Disorder Warning Signs

Sleep disorders beyond insomnia require medical evaluation. Sleep apnea, where breathing repeatedly stops during sleep, causes poor sleep quality, morning headaches, and excessive daytime sleepiness. Risk factors include snoring, gasping during sleep reported by roommates, waking with dry mouth or sore throat, and morning headaches.

Research shows that untreated sleep apnea reduces academic performance by 35-45% through cognitive impairment from fragmented sleep. College health services can arrange sleep studies to diagnose these conditions.

Restless leg syndrome, causing uncomfortable sensations in the legs that worsen at night, prevents sleep initiation. This affects 5-10% of young adults and responds well to treatment when properly diagnosed. Narcolepsy involving excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden sleep attacks typically emerges in late teens to early twenties, making college years common for first symptoms. These conditions require medical diagnosis and treatment beyond sleep hygiene improvements.

Circadian rhythm disorders, where your internal clock doesn't align with conventional schedules, create chronic sleep problems. Delayed sleep phase disorder causes extreme night owl tendencies where you can't fall asleep until 2-4 AM, regardless of efforts. This affects 7-10% of young adults and responds to specialized treatments, including light therapy and melatonin timing. If you consistently can't sleep before 3-4 AM but feel fine sleeping late morning to afternoon, evaluation for circadian rhythm disorders may be warranted.

3. Mental Health and Sleep Interconnections

Sleep problems and mental health conditions frequently co-occur, requiring integrated treatment. Depression commonly causes early morning awakening and non-restorative sleep. Anxiety disorders create difficulty falling asleep and nighttime rumination. When sleep problems accompany persistent low mood, loss of interest in activities, excessive worry, or panic symptoms, a mental health evaluation becomes essential.

Research shows that 60-70% of students with major depression experience significant sleep disturbances, while 40-50% of those with anxiety disorders report chronic insomnia.

Treating underlying mental health conditions often improves sleep, while improving sleep can reduce anxiety and depression symptoms. The relationship works bidirectionally, making it important to address both rather than viewing sleep as separate from mental health. Campus counseling centers provide integrated care addressing both concerns simultaneously. Studies demonstrate that students receiving combined treatment for depression and insomnia improve faster with more sustained benefits than those receiving either treatment alone.

Suicidal thoughts or self-harm urges, especially if accompanied by sleep disturbances, require immediate professional help. Severe sleep deprivation can worsen these thoughts through effects on mood regulation and impulse control. If experiencing these symptoms, contact campus crisis services, call 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or text HOME to 741741 for Crisis Text Line. Sleep problems contributing to mental health crises need professional intervention to ensure safety while establishing healthy sleep patterns.

When Academic Demands Make Sleep Impossible

Sometimes sleep problems stem from genuinely unsustainable academic workload rather than sleep hygiene issues. If you've optimized sleep habits but consistently need to sacrifice sleep to meet academic demands, the problem requires addressing workload rather than sleep strategies. This might mean dropping a class, reducing work hours, or seeking academic accommodations. Research shows that students attempting to maintain 18-20 credit loads while working 20+ hours weekly achieve worse outcomes than those with more sustainable schedules, even if the former sleep less to fit everything in.

When facing temporary periods of genuinely excessive demands like finals week or major project deadlines, strategic delegation of lower-priority work preserves sleep for cognitive function. Using a reliable essay writing service for assignments in less critical courses during peak-demand periods allows you to maintain adequate sleep for exam preparation and high-stakes work rather than sacrificing rest attempting everything impossible. This approach treats sleep as the essential foundation for performance rather than an optional luxury to sacrifice first.

Talk with academic advisors about workload concerns. Many schools offer reduced course load options, incompletes for temporary overload situations, or medical withdrawals preserving GPA when circumstances prevent success. Prioritizing sustainable long-term success over attempting to muscle through unsustainable schedules protects both your health and your academic record better than exhausting yourself into breakdown.

Key Takeaways

Quality sleep provides the foundation for academic success, physical health, and emotional wellbeing, making it essential rather than optional:

- College students need 7-9 hours of nightly sleep, but 60-70% average only 5-6 hours, creating chronic sleep deprivation that impairs cognitive function equivalent to intoxication

- Sleep deprivation reduces memory consolidation by 25-40%, impairs attention and focus, causing 30-50% more errors, and weakens decision-making and executive function

- Evidence-based sleep strategies include consistent sleep-wake times within 30-minute daily windows, cool dark quiet sleeping environments, 2 PM caffeine cutoff, and 60-90 minute screen-free wind-down periods

- Sleep problems lasting more than 3-4 weeks despite good sleep hygiene require professional evaluation for potential sleep disorders or underlying mental health conditions

- When academic demands genuinely prevent adequate sleep, adjusting workload protects health and performance better than sacrificing sleep by attempting impossible schedules

The single most impactful change most college students can make for academic performance and wellbeing is prioritizing consistent, adequate sleep. This requires treating sleep as a non-negotiable foundation for everything else rather than a flexible resource to sacrifice when demands increase. While optimizing sleep hygiene helps tremendously, some situations involve genuinely unsustainable workload requiring strategic choices about what receives your limited time and energy.

During particularly demanding academic periods, maintaining sleep for cognitive function sometimes means making difficult choices about assignment completion. Recognizing when workload exceeds sustainable capacity and seeking appropriate support, whether through professors, advisors, counseling services, or strategic use of resources like academic support services, preserves both your immediate performance and long-term health rather than exhausting yourself attempting everything perfectly while sleep-deprived.

Your brain and body require sleep to function properly. No amount of caffeine, willpower, or dedication can substitute for the restoration that occurs during adequate sleep. Prioritizing sleep isn't laziness or weakness; it's recognition that sustainable high performance requires taking care of the biological systems enabling that performance.