Why your conclusion matters more than you think

Your introduction gets readers to start your essay. Your body paragraphs present your evidence. But your conclusion determines what readers remember and how they feel about your argument when they finish reading.

Research on reading comprehension shows that people remember the first and last things they read better than anything in the middle, a phenomenon known as the primacy and recency effects. Your conclusion benefits from recency bias, meaning it has disproportionate impact on your reader's overall impression of your essay.

What happens when conclusions fail

When you write weak conclusions, readers finish your essay feeling unsatisfied, like watching a movie that just stops without resolution. Professors unconsciously lower their assessment of your entire essay when conclusions feel rushed or mechanical, even if your body paragraphs were strong. The conclusion signals whether you fully understood your own argument's significance or just completed the assignment as a checklist item.

Weak conclusions share predictable patterns: starting with "In conclusion," copying the thesis word for word from the introduction, listing body paragraph topics without synthesis, introducing completely new information, ending abruptly without perspective, and apologizing for limitations ("This essay only scratched the surface").

What strong conclusions accomplish

Strong conclusions create synthesis, showing how your separate arguments connect and build on each other rather than treating them as isolated points. They demonstrate significance by explaining why your argument matters beyond the immediate essay topic. They provide closure by creating satisfying symmetry with your introduction while showing how far you've traveled intellectually.

The best conclusions leave readers thinking about your ideas after they finish reading, not because you explicitly told them what to think, but because you showed them connections they hadn't considered before.

Your Conclusions Feel Rushed or Repetitive?

Professional essay writers understand that conclusions aren't about summarizing, they're about elevating your argument:

- Synthesis strategies that show how your points connect and build

- Significance framing that explains why your argument matters

- Natural closure that satisfies readers without feeling forced

- Expert guidance on conclusion techniques for different essay types

Transform weak endings into memorable final impressions.

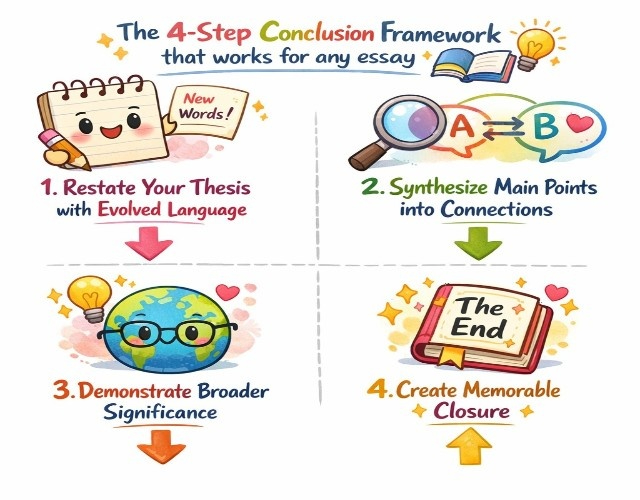

Order NowThe 4 step conclusion framework that works for any essay

This systematic approach works across essay types and topics, argumentative, analytical, narrative, or research essays. Follow these four steps in order:

Step 1: Restate your thesis with evolved language

Begin by revisiting your thesis statement from your introduction, but, this is critical, don't copy it word-for-word. Your introduction's thesis stated what you intended to prove. Your conclusion's restated thesis confirms what you successfully demonstrated.

Why paraphrasing matters:

Word for word repetition signals that you haven't intellectually progressed from introduction to conclusion. It feels mechanical and lazy. Paraphrasing your thesis using fresh language shows you've internalized your argument deeply enough to express it multiple ways.

Your evolved thesis should reflect the journey your essay has taken. If your introduction thesis was tentative ("This essay will argue"), your conclusion thesis should be confident ("This analysis has demonstrated"). If your introduction posed a question, your conclusion states the answer.

Examples of effective thesis evolution

Notice how the conclusion thesis is more specific and confident, it doesn't just restate the claim but integrates the evidence presented throughout the essay. The conclusion thesis synthesizes the evidence while showing deeper understanding than the introduction promised.

Common mistakes to avoid:

Starting with clichéd phrases like "In conclusion," "To sum up," "In summary," or "As this essay has shown" wastes valuable space and signals weak writing. These phrases are unnecessary because your conclusion's position at the end already tells readers you're concluding. Copying your introduction thesis word for word makes readers wonder why they bothered reading the essay if you're saying exactly the same thing you started with. Making your restated thesis longer and more complex than necessary. Aim for 1 to 2 sentences maximum before moving to synthesis. |

Step 2: Synthesize main points into connections

Synthesis is what separates strong conclusions from weak ones. Don't just list your body paragraph topics; show how they connect, build on each other, or create cumulative impact.

The difference between summary and synthesis:

Weak summary (mere list): "This essay discussed three effects of social media: comparison anxiety, sleep disruption, and loss of social skills."

This tells readers what topics you covered, but not what those topics mean together.

Strong synthesis (shows connections): "These three mechanisms, comparison driven anxiety, algorithmic sleep disruption, and social skill erosion, work together synergistically. Sleep-deprived teenagers become more vulnerable to comparison anxiety, while both factors make face to face interaction feel more difficult, creating a vicious cycle that compounds mental health damage."

This shows how your separate points interact and reinforce each other, creating insight beyond what any individual paragraph provides.

How to create an effective synthesis:

Identify relationships between your main points. Do they build chronologically? Do they represent different aspects of a larger problem? Do they create a chain of cause effect relationships? Do they present escalating severity? Use connective language that shows relationships: "These factors combine," "This dynamic reinforces," "Together these mechanisms create," "Each point builds on the previous." For essays with 3 to 4 main points, dedicate 2-3 sentences to synthesis. For longer research papers with many supporting arguments, focus on synthesizing the 2-3 most important contributions rather than trying to touch on everything. |

Step 3: Demonstrate broader significance

After synthesizing your main points, explain why your argument matters beyond the immediate essay topic. This "so what?" moment is what makes conclusions feel substantial rather than perfunctory.

Types of significance you can demonstrate:

a. Practical implications: What real-world actions or changes does your argument suggest?

"Understanding these social media mechanisms has immediate practical applications for parents, educators, and policymakers designing interventions to protect adolescent mental health."

b. Broader context: How does your specific argument connect to larger issues or debates?

"While this analysis focused on adolescent social media use, the underlying pattern, technology designed to maximize engagement regardless of user wellbeing, extends to streaming services, mobile games, and nearly every digital platform competing for attention in the modern economy."

c. Future consequences: What happens if we accept or reject your argument?

"If current trends continue without intervention, we're not just risking individual mental health outcomes; we're potentially creating a generation that struggles with fundamental social skills required for collaborative work, civic participation, and intimate relationships."

d. Theoretical implications: How does your analysis challenge or support existing understanding?

"This evidence challenges the popular narrative that technology is neutral and effects depend entirely on how we use it. When platforms are engineered specifically to exploit psychological vulnerabilities, user choice becomes largely illusory."

e. Research questions: What questions does your analysis raise that deserve further investigation?

"These findings suggest several directions for future research: How do social media effects differ across cultures with varying privacy norms? At what age do these vulnerability patterns first emerge? Which specific design features contribute most to harm?"

How much significance to include:

For short essays (500 to 750 words), aim for 2 to 3 sentences of significant discussion. For medium essays (1,000 to 1,500 words), aim for 3 to 5 sentences. For long research papers (2,000+ words), you might dedicate an entire paragraph to implications and future directions. The key is proportionality; don't spend more time on significance than you spent on synthesis. Both elements matter, but synthesis should come first and typically receives slightly more space. |

Step 4: Create memorable closure

End your conclusion (and essay) with a final sentence that provides satisfying closure while leaving readers thinking about your ideas.

Effective closing techniques:

A. Call to action (works best for persuasive essays):

"The evidence is clear, it's time for policymakers to regulate social media algorithms the way we regulate food safety, pharmaceutical marketing, and other products that affect public health."

B. Provocative question (raises implications without lecturing):

"If we've created technology that measurably harms adolescent mental health in exchange for corporate profits, what does that reveal about our society's values?"

C. Looking forward (projects into the future):

"The next generation will inherit a world where digital interaction is unavoidable. Whether technology enhances or diminishes their wellbeing depends on choices we make now."

D. Circular closure (connects back to the introduction hook):

If your introduction opened with a student's story about social media anxiety, your conclusion might return to that story:

"When Sarah checks Instagram compulsively at 2 AM, she's not making a bad personal choice; she's responding exactly as platform designers intended. Understanding this dynamic is the first step toward designing healthier digital environments."

E. Powerful quote (use sparingly and only when genuinely relevant):

"As Marshall McLuhan warned decades before social media existed, 'We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.' The question is whether we'll recognize what we're being shaped into before the transformation is complete."

Techniques to avoid in closing sentences:

- Apologetic hedging: "Of course, this is just one perspective," "These are only my opinions," "This essay only scratched the surface."

- New information: "Another factor worth considering is..." Save new points for the body, and conclusions synthesize existing arguments.

- Obvious statements: "In conclusion, this is an important topic," "These are complex issues," "More research is needed."

- Melodramatic overstatement: "If we don't act immediately, civilization will collapse!" Match your tone to your evidence.

Essay specific conclusion strategies

Different essay types require adapted conclusion approaches:

1. Argumentative essay conclusions

Argumentative conclusions need forceful final statements that leave no doubt about your position's validity. After presenting your synthesis, include a call to action or policy recommendation that flows naturally from your argument.

Example: "The evidence overwhelmingly supports implementing a universal basic income. Cash transfers reduce poverty more efficiently than means-tested programs, stimulate local economies through increased consumer spending, and address technological unemployment that will only accelerate. The question isn't whether we can afford UBI, it's whether we can afford not to implement it as automation eliminates millions of traditional jobs over the next decade." |

This conclusion restates the thesis (UBI should be implemented), synthesizes the three main arguments (efficiency, economic stimulus, technological unemployment), demonstrates significance (automation makes this increasingly urgent), and provides closure through a reframed question that challenges common objections.

2. Analytical essay conclusions

Analytical conclusions should synthesize multiple interpretations or highlight your analysis's most significant insight. Focus on what your close reading revealed that surface-level understanding misses.

Example: "Fitzgerald's use of weather imagery throughout The Great Gatsby reveals more than Gatsby's emotional state; it demonstrates how environment and psychology blur together when pursuing impossible dreams. The progression from spring's hope through summer's intensity to autumn's decay mirrors Gatsby's trajectory while suggesting that his downfall was environmentally determined, not personally chosen. By making weather an active force rather than a passive backdrop, Fitzgerald argues that the American Dream itself is a seasonal delusion, beautiful in promise, destructive in fulfillment, doomed to fade." |

This analytical conclusion synthesizes the essay's close readings of weather imagery, demonstrates broader significance about the American Dream theme, and offers insight that elevates the argument beyond "Fitzgerald uses weather symbolically."

3. Narrative essay conclusions

Narrative conclusions should be reflective rather than summative. Show what you learned, how you changed, or what the experience means in retrospect. The conclusion is where personal stories gain broader meaning.

Example: "That summer working at my grandmother's restaurant taught me something economics textbooks never could: value isn't determined by market price. The regulars who came daily for $3 coffee and conversation were buying community, not caffeine. Fifteen years later, as I design pricing strategies for a tech startup, I still remember those transactions. Sometimes the real product isn't what's on the menu." |

This narrative conclusion reflects on the experience's meaning, shows lasting impact, and connects a personal story to broader truths about economics and human behavior.

4. Research paper conclusions

Research conclusions often suggest questions for future study or discuss limitations and implications of findings. Acknowledge what your research can and cannot claim.

Example: "This study provides preliminary evidence that mindfulness meditation reduces anxiety in college students, with effect sizes comparable to cognitive behavioral therapy. However, the small sample size (n=47) and single-institution focus limit generalizability. Future research should examine whether effects persist beyond the 8-week intervention period, how mindfulness compares to combined approaches, and whether benefits extend to clinical anxiety disorders. Additionally, neuroimaging studies could illuminate the neurological mechanisms underlying observed anxiety reduction. Despite these limitations, this research supports integrating mindfulness programs into student mental health services." |

This research conclusion restates findings, acknowledges limitations honestly, suggests specific future research directions, and explains practical implications, all elements expected in academic research writing.

Most students struggle with synthesis because they treat body paragraphs as independent units rather than parts of a larger argument. If you find synthesis difficult, that's a red flag that your essay might lack cohesion. Our professional essay writing service helps students see the connections between their own points and teaches synthesis techniques that transform adequate essays into compelling arguments.

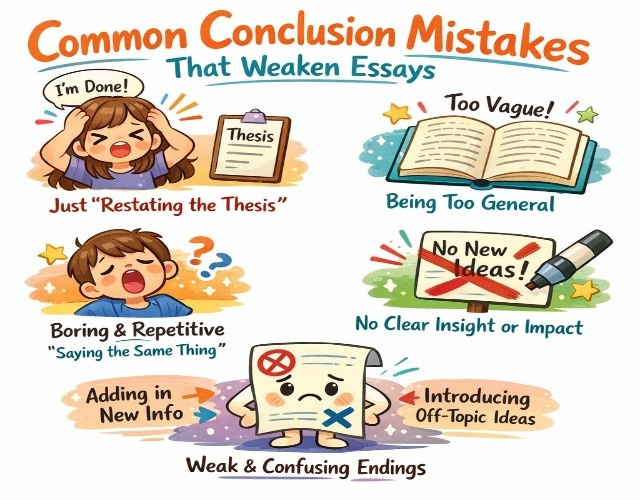

Common conclusion mistakes that weaken essays

Mistake #1: Introducing completely new information

Your conclusion should synthesize and reflect on arguments already made, not present new evidence or entirely new points. Readers feel frustrated when conclusions suddenly pivot to topics the essay never addressed.

Wrong: "Beyond social media's mental health effects, we must also consider privacy violations, election interference, and misinformation spread..."

These are valid topics, but if your essay didn't discuss them, don't introduce them in your conclusion. Stick to synthesizing what you actually argued.

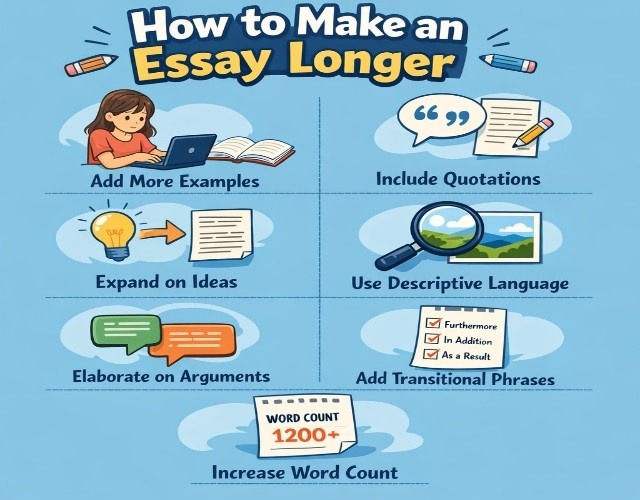

Mistake #2: Making your conclusion too short

A one or two sentence conclusion feels abrupt and signals you ran out of time or ideas. Conclusions should comprise approximately 10-15% of your total essay length:

|

The "30 to 60 second read-aloud test": Your conclusion should take 30 to 60 seconds to read aloud at a natural pace for most academic essays.

Mistake #3: Simply copying your introduction

Some students write conclusions that mechanically repeat introduction sentences with minor word substitutions. This makes readers wonder why they read the essay if you haven't progressed intellectually from start to finish.

Your conclusion should feel evolved, more sophisticated, more specific, and more confident than your introduction because you've now supported your claims with evidence and analysis.

Mistake #4: Apologizing or undermining your argument

Phrases like "This essay only scratched the surface," "These are just my opinions," and "Of course, there are many other perspectives" undermine the authority you spent the entire essay building.

If your argument is solid, state it confidently. If you have legitimate limitations to acknowledge (particularly in research papers), frame them as opportunities for future research rather than reasons to doubt your conclusions.

Mistake #5: Making melodramatic claims unsupported by your evidence

Don't suddenly claim world-changing significance if your essay presented moderate evidence about a narrow topic. Match your conclusion's ambition to your actual argument's scope.

Wrong: "If we don't solve social media addiction immediately, human civilization will collapse within a generation." This is wildly disproportionate to an undergraduate essay analyzing social media effects on sleep patterns. Right: "Understanding social media's effects on adolescent sleep has immediate applications for parents, educators, and pediatricians designing healthy technology habits." This claims reasonable significance, supported by the evidence you actually presented. |

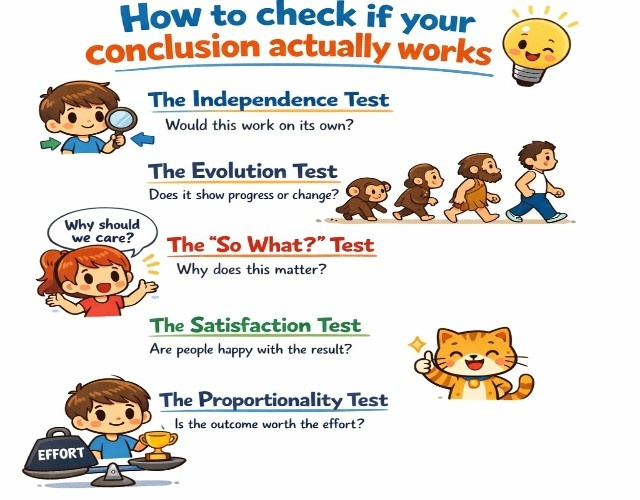

How to check if your conclusion actually works

After drafting your conclusion, use these diagnostic tests:

1. The independence test: Can someone understand your essay's main argument by reading only your conclusion? If yes, your conclusion successfully synthesizes your key points. If no, you've probably written a vague closing that doesn't actually capture your argument.

2. The evolution test: Compare your conclusion thesis to your introduction thesis. Does the conclusion version show intellectual progression? Are you more specific, more confident, more sophisticated in your conclusion? If the two versions are interchangeable, revise for evolution.

3. The "so what?" test: Does your conclusion answer why your argument matters? If a reader asks "So what?" after finishing, you haven't demonstrated significance effectively.

4. The satisfaction test: Does your conclusion feel like a natural endpoint, or does it feel abrupt and unfinished? Read your final body paragraph and conclusion together. Does the transition feel smooth? Does the closing sentence create a sense of completion?

5. The proportionality test: Is your conclusion approximately 10 to 15% of your total essay length? Conclusions that are too short (under 10%) feel rushed. Conclusions that are too long (over 20%) become repetitive and lose focus.

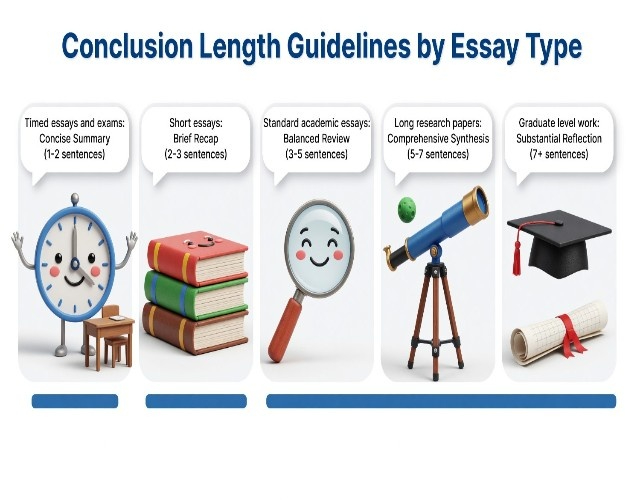

Conclusion length guidelines by essay type

Different assignments require different conclusion approaches

1. Timed essays and exams: When time is limited, prioritize thesis restatement and brief synthesis (2 to 3 sentences). Skip elaborate significance discussion, professors understand time constraints. A strong 3 sentence conclusion beats a rushed, incomplete paragraph.

2. Short essays (500 to 1,000 words): Focus on clear thesis restatement and tight synthesis. You have limited space, so significant discussion should be concise (1 to 2 sentences) rather than elaborate.

3. Standard academic essays (1,500 to 2,000 words): Include all four conclusion elements: evolved thesis, synthesis of main points, significance discussion, and memorable closing. This is where the full framework works best.

4. Long research papers (3,000+ words): Expand your conclusion to include a detailed limitations discussion, specific future research directions, and thorough implications analysis. These papers often have conclusion sections rather than single paragraphs.

5. Graduate level work: Expectations increase. Synthesis should demonstrate sophisticated understanding of how your arguments interact. Significance should connect to theoretical frameworks or disciplinary debates. Future directions should be specific and actionable.

Stop Submitting Essays with Weak, Rushed Conclusions

Your conclusion is your final opportunity to show readers why your argument matters

- Strategic synthesis that connects your points meaningfully

- Significance demonstration that elevates beyond summary

- Memorable closure that creates lasting impressions

- Essay-type-specific approaches that match assignment requirements

Don't let weak conclusions undermine strong essays.

Order NowFinal thoughts on conclusion mastery

Here’s what matters most: conclusions aren’t chores or afterthoughts. When you’ve developed strong arguments throughout your essay, conclusions practically write themselves; you’re simply showing readers how your ideas fit together and why they matter. Any effective essay writing guide emphasizes that strong conclusions grow from strong arguments.

If you struggle with your conclusion, the problem often lies earlier in your essay. Perhaps your thesis isn't clear enough, your main points don't connect well, or you haven't fully considered your argument's significance. Strong conclusions emerge naturally from well-constructed essays.

The four-step framework, restating thesis, synthesizing points, demonstrating significance, and creating closure, provides a reliable structure that works across essay types and topics. Master this framework, and you'll transform adequate essays into memorable work that resonates long after readers finish.

Remember that your conclusion is the last thing your professor reads before deciding your grade. It has a disproportionate impact on final impressions. Investing extra effort in your conclusion, carefully evolving your thesis, synthesizing connections between points, explaining significance thoughtfully, and crafting a memorable closing sentence can materially improve your grade.

The difference between B essays and A essays often comes down to conclusions. B essays summarize competently but don't elevate their arguments. A essays synthesize insights and demonstrates significance in ways that make readers think. With practice using this four-step framework, you can consistently write conclusions that turn your essays into the latter.

-20154.jpg)